The COVID-19 pandemic forced educators and administrators across the globe into an uncomfortable but necessary pivot: immediate digital transformation. Virtually overnight, classrooms were replaced by screens, lesson plans moved online, and teachers became tech support. While the crisis eventually faded, it revealed something long overdue, we must build resilient, scalable systems for continuity of instruction, not just for emergencies, but for the evolving reality of digital learning.

As we look beyond the pandemic, the question isn't if remote learning will be needed again, but how prepared we’ll be when it is. Chapters 10–12 of Teaching and Learning at a Distance by Simonson and Zvacek (2024) emphasize the importance of infrastructure, planning, and instructional leadership in building durable online learning systems. This paired with insights from national education organizations and the Crisis Schooling Rubric, three critical priorities stand out: digital equity, teacher training and support, and instructional design for engagement.

1. Digital Equity Is Non-Negotiable

One of the most glaring disparities during the pandemic was access, or the lack of it. Reviewing the Crisis Schooling Rubric, it shows that many schools initially lacked the tools to support students equitably. The highest level of performance included not just device access, but consistent internet, tech support, and integration of learning platforms like ClassLink to streamline logins and access.

The SETDA eLearning Coalition emphasizes that digital equity must go beyond distribution. In their guide, they urge districts to “design for digital inclusion, not just digital access,” advocating for device durability, multiple learning formats, and offline access strategies.

Simonson and Zvacek (2024) reinforce this in Chapter 11 explaining that infrastructure is the foundation of distance education. Without reliable access to content and platforms, proper learning cannot occur. Thus, planning for continuity must include investments in long-term technology access, community partnerships, and alternative formats for those without reliable internet.

2. Teacher Readiness Determines Continuity

The Professional Capacity & Development tab of the Crisis Rubric makes it clear that effective continuity planning must include comprehensive, ongoing training for educators. Teachers don’t just need tech tutorials—they need support in rethinking pedagogy for digital spaces. The CoSN Education Continuity Report explains that teachers need more than platforms; they need practice using those platforms to teach with clarity and engagement.

Educators must be trained to:

-

Scaffold learning for digital environments.

-

Foster student interaction remotely.

-

Deliver timely, actionable feedback online.

In my own district, we found that tech-savvy teachers weren't always the most effective online instructors, those who embraced collaboration and feedback loops with students thrived. As the ClassLink Guidebook notes, ongoing professional learning must be “embedded into school culture, not simply added in response to crisis.”

3. Instructional Design Must Center on Engagement

The third standout issue from the rubric is in the Curriculum & Instruction tab. Many schools initially provided content but not connection. Students were given packets or static online lessons with little engagement or interaction.

As we prepare for future remote or hybrid models, we must go beyond simply uploading lessons. We must design experiences that are intentional, motivating, and rooted in best practices.

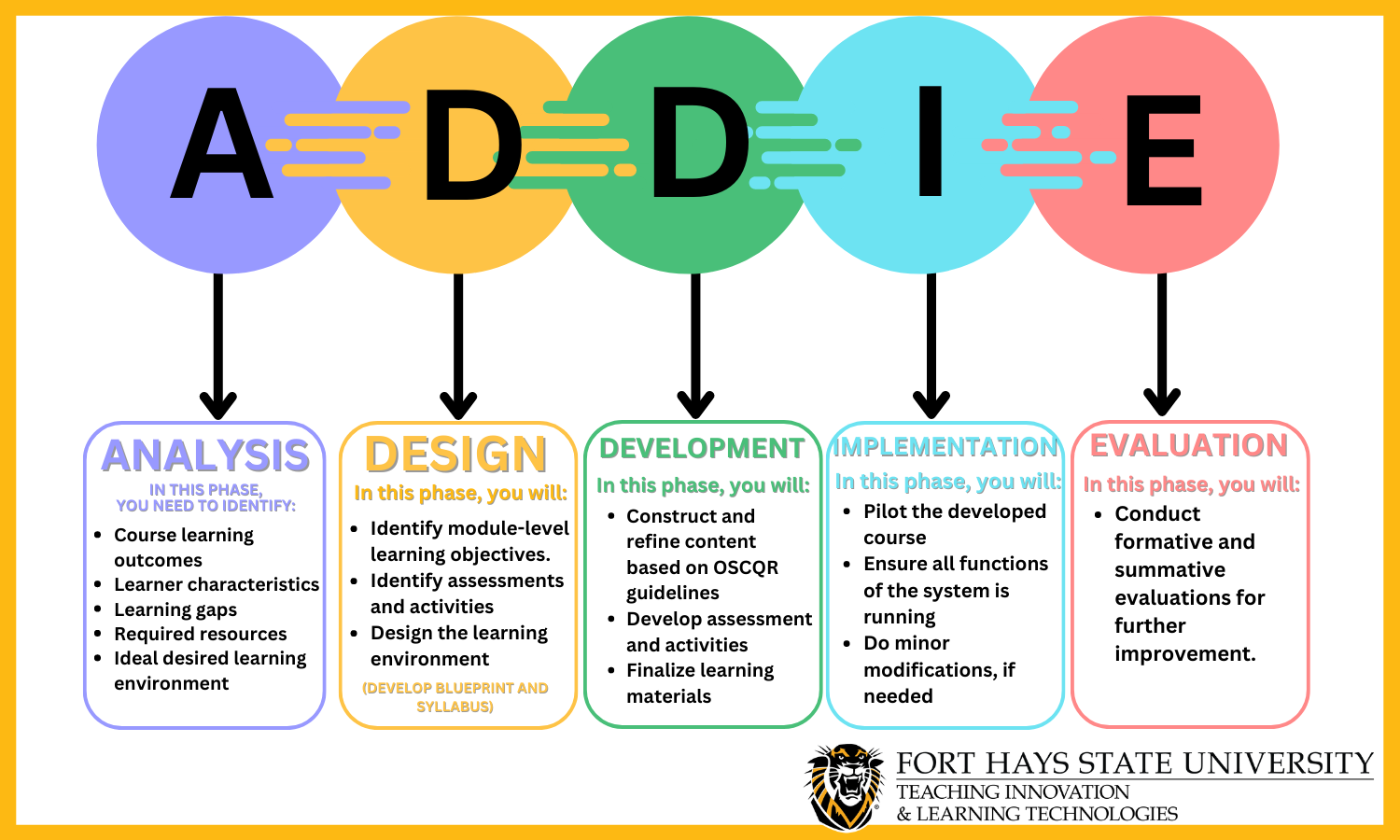

A powerful framework for doing this is the ADDIE model (Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, Evaluate) and Gagné’s Nine Events of Instruction, both of which offer structured approaches to building engaging online learning environments. Rather than treating these models as theoretical, they should be applied practically to ensure lessons include attention-grabbing introductions, clear objectives, guided practice, assessment, and feedback.

According to Branch (2009) in Instructional Design: The ADDIE Approach, “the ADDIE model supports iterative, flexible design that enables instruction to be learner-centered and performance-focused, even across digital platforms” (p. 2). Similarly, Gagné’s model ensures cognitive engagement at every phase of learning—from gaining attention to promoting retention and transfer.

(For more on Gagne's model, see the video below)

By applying these models, educators can develop lessons that do more than deliver information, they build understanding, promote interaction, and foster motivation, even when delivered remotely. SETDA’s eLearning Coalition also echoes this, advocating for project-based learning, multimedia integration, and meaningful digital assessment as core design strategies.

Conclusion: Continuity as Culture, Not Crisis

Conclusion: Continuity Is a Mindset, Not a Moment

The pandemic may have brought urgency, but it also brought clarity in that continuity planning is not about a moment of crisis, it’s about creating systems that can flex and function in any context. Whether due to a snowstorm, a hurricane, or a global event, students deserve learning experiences that are uninterrupted, high-quality, and engaging.

The rubrics, resources, and research available now provide us with a blueprint. The question is whether we’ll build on it—intentionally, equitably, and with foresight.

Resources:Branch, R. M. (2009). Instructional design: The ADDIE approach. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09506-6

ClassLink. (2021). Learning Continuity Guidebook. https://www.classlink.com/solutions/remote-learning

Consortium for School Networking (CoSN). (2021). Digital Equity Report. https://www.cosn.org/

Educational Continuity Planning Rubric. (2020). Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1lXAwsLWBfNslkhIGxHqgojVjmV5n8KIrR7SCmZnNqsA

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Simonson, M., & Zvacek, S. (2024). Teaching and learning at a distance: Foundations of distance education (8th ed.). Information Age Publishing.

SETDA. (2022). eLearning Coalition. https://www.setda.org/main-coalitions/elearning/